Do the Wild Animals in Our Backyards Deserve Our Mercy?

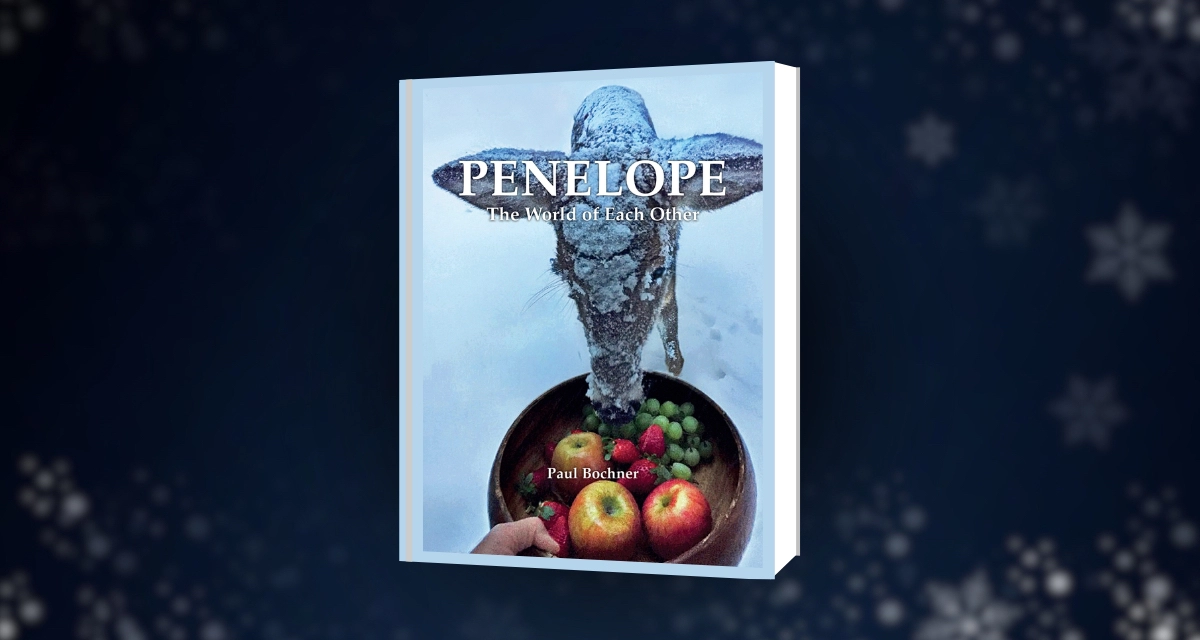

“Penelope: The World of Each Other,” Compass Rose Publishing

By Paul Bochner

Release Date: October 28, 2025

Review by Wayne Pacelle

If you love animals, you’re neither unusual nor eccentric. You’re in good company — firmly in the mainstream of social behavior and thought. Human beings need others for emotional well-being. Animals, as it turns out, are part of that social support network — an antidote to loneliness and the eraser of social isolation.

For our emotional health and resiliency, humans crave romance, kinship with family, and social experiences with friends, but fulfillment also comes in heaps from dogs, cats, horses, and other animals. Widening the lens to see and experience other life forms, we are also drawn to the glories of nature and the dazzling forms of wildlife who inhabit our world. Animals who act on nature’s stage are a wellspring of awe.

The bond between humans and other animals and nature is “biologically encoded,” said the Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson, who coined the theory of “biophilia” to explain our love of life. “From infancy,” he explained, “we concentrate happily on ourselves and other organisms. We learn to distinguish life from the inanimate and move toward it like moths to a porch light.”

That moth-to-flame impulse has so many expressions in contemporary society — whether the routine of inviting cats and dogs to prowl our homes and occupy our beds, catching the remarkable feats of flight of birds or spotting a fin or fluke of a giant whale, or volunteering at one or more of 35,000 charities devoted to helping just about every kind of creature.

Some of these expressions of the bond may be peculiar to our age, but our connections with animals are a long-running centerpiece of the human story. That relationship with animals has been tangled and contradictory, swinging between affection and raw exploitation.

But the pro-social connection is unyielding — across our long journey as hunters and gatherers, through the era of animal domestication and revolutions in herding and agriculture, and into the industrial age and now into the digital age, when our immersion in technology and other human designs causes us to compensate even more urgently and to crave touch with the nonhuman world.

Biochemistry, as with so many human behaviors, partly explains the connection. Just like adrenaline or cortisol surges at the sight of an intruder or a powerful animal, or testosterone or estrogen drives sexual attraction, there are biochemical explanations for affections and the lure of animals and nature.

The neuropeptide oxytocin is known to promote maternal care in animals, driving a mother to exhibit extreme fascination, focus, and care of the newly born. But oxytocin does not just circulate in the bloodstream during childbirth and post-partum nursing. It’s always coursing through our veins, as are vasopressin and other pro-social hormones. These hormones help us identify faces and exude warmth toward others. They appear to have stress-relieving effects, such as lowering blood pressure and anxiety.

“Penelope: The World of Each Other” starts as a socially distanced and unconventional animal rescue story that morphs into a love story, infused with meditations on animal cognition, emotions, and the travails of animals.

Into this long drama of human-animal relations comes Paul Bochner, with his own very distinct expression of a potent connection to nonhuman lives. He’s the author of a deeply sensitive, surprising, and insightful book that explores the power and pain of the human-animal bond. “Penelope: The World of Each Other” starts as a socially distanced and unconventional animal rescue story that morphs into a love story, infused with meditations on animal cognition, emotions, and the travails of animals.

The book is a seemingly linear account of man-meets-deer on a small backyard stage, but Bochner digs deep into the many angles of the human-animal bond, with the read an emotional roller-coaster for me. Feelings of pity and joy swirled and quelled and then swirled again. Bochner inspired me with his courage to befriend a fawn in crisis, and the bond between them was born starting with Bochner’s first act of kindness to an animal in crisis.

By the end of this compact read — with pictures that reminded me of amateur photo albums from my childhood in the 1970s, designed to memorialize special moments for the decades ahead — I was feeling both spent and vital. Avoiding polemical thought, or even a whiff of a treatise or a screed against hunting and habitat degradation, Bochner fills his book with life lessons and problem-solving, especially as he confronts more than a few moral forks in the road.

In his backyard, Bochner meets a starving fawn, with one forelimb disfigured and the other misshapen by compensating for it. When he first laid eyes on her, the author gauged that the weakened, shrunken, hobbled fawn was nearing her earthly end. Driven by mercy, Bochner comes to her aid with food in hand. Grapes, apples, berries. The food offerings were akin to throwing a life buoy to a drowning little girl.

“Before I knew I was doing so, I had placed myself in the literal center of the drama of a mother rejecting her child,” writes the author. Bochner comes to understand that Penelope, the name he fixed on her, had been abandoned by her mother. Stacking the deck even more against Penelope, her mother had turned into an enemy, charging at Penelope with lethal intent. Her mother, Castle, had two other fawns, Mr. Bochner suggested, and wanted nothing to do with the disabled daughter.

He watched in horror, more than once, as Penelope awkwardly scrambled away when her mother gave her the bum’s rush. Bochner imagines she must have felt like the loneliest little deer in the world — crippled, abandoned, and assaulted. This was a mom whose testosterone, rather than her oxytocin, was now flowing with a glance at her child.

Bochner chose the path of guardian human, defending her from Castle and any other deer and from coyotes and foxes and other creatures or circumstances that menaced her. I even imagined Bochner chasing off bees, should the fragile deer bump into a hive.

This man was no bystander. He got muddy. He fed the hungry. He defended the weak. Was he wrong to take this kind of action with wild animals, where life and death are the features of the natural order? Or was he more morally alert and engaged than the rest of us who see a family of deer in our backyard or in a park and treat their condition as the hand that nature dealt? Take any sample of 1,000 people, put them in his place, and I bet not one of them would have chosen any course of action that would have resembled his own.

Deer leap over the fence in my suburban backyard, and I love watching them. They are welcome. And when I choose to let out my hound, I check for any sight of them and often scoop up Asher and walk the perimeter to make sure no deer are bedded down. He’s programmed for chasing, to the detriment of the deer.

But I leave it at that. I’ve not dug into the social relationships of the animals who are passers-by, and I don’t try to give them any leg up on life. I just try to minimize the possibility of needless risk.

My wife occasionally puts out some food for them, especially during the winter, but I’m hands-free when it comes to the deer and the foxes, who are also frequent visitors. A “welcome” sign, no adverse actions, but no food supplements, water, human-made shelter for them.

Leave deer and other wildlife to their own wits, I’ve long thought. But are there any exceptional circumstances that warrant Bochner’s kind of engagement? Inattention meant death in Penelope’s case. Hand-outs gave Penelope more life, and the attendant human attention and concern nourished Penelope.

“Penelope: The World of Each Other” is a chronicle of several years of engagement for Bochner and the deer in his world. Bochner was up at dawn every day with fruit and vegetables and mast crops in hand. Warm chestnut soup was a Bochner specialty and a Penelope favorite.

But the cone of protection had its limits. Bochner did not turn his backyard into a petting zoo.

After the feeding and some social time, Penelope would leave the property and explore parts unknown to Bochner. Ongoing engagement required Penelope to return to the backyard and the back door:

The moment Penelope appears, I am relieved, and the word “relief” carries multiple meanings. She relieves me of my own burdens. If I awaken on a given morning to thoughts of self, to remorse or self-recrimination, the instant I begin to care for her my thoughts are directed toward her and away from myself. Giving her the touch of my hand or the taste of chestnuts, seeing her pleasure, I am filled with pleasure inseparable from hers. By letting go of my aspect of the moment, by entering as much as possible into her aspect, I feel ecstasy; literally, being outside myself.

For Bochner, this was not just a rescue mission. This was a labor of love, grounded on deep emotional affection, but with limits.

One way that we create emotional distance from animals, to clear the path for indifference or even cruelty, is to reduce them to the equivalent of animal automatons, engaged in an endless pursuit of food, space, and mates and driven only by the designs of evolution, as if the animals’ feelings and emotions are somehow different and less relevant than our own. As Bochner reminds us, however, we are all mammals and made of the same stuff:

The list of what unites living creatures is long, the list of what divides us is brief. The more time I spend with Penelope the more I marvel at what we share. Biologically, our structural and organic components are essentially identical. Skull, jaw, teeth, spinal column, vertebrae, limb bones, ribs, muscles, tendons, joints, ears, eyes, nostrils and olfactory organs, tongue, lungs, digestive system, a beating heart, arteries, veins, capillaries, nerves, skin, and hair. Her brain and mine each process actions, learned, adaptive, and reflexive responses, and memory.

There are plenty of skeptics who might diminish or even demean his labors and sacrifices for Penelope. But let’s remember that it was long the norm to keep our pets outside, free-roaming or chained, tethered, or fenced, perhaps with a modest doghouse for rudimentary shelter. Today it’s the norm to give them the run of the main house, with heat, beds, fresh water, and other creature comforts. Many of us spend a small fortune on veterinary care, and many dogs and cats are now on pet health plans to enable specialized veterinary care for ongoing preventative and emergency care.

Is the anxiety and compassion Bochner exhibits for deer any less worthy than the concern millions of pet owners express for a dog or a cat, or a horse lover for their stallion or mare? The norms of society tell us to tend to the needs of the domesticated animals in our homes or protected pastures, but what about the wild animals outside?

The network of wildlife rehabilitation centers in our nation grows every year, a safety net for those of us who come across an animal struck by a car or truck, concussed after flying into a window, mauled by a predator, or tangled in an electrical line. There’s little controversy about our merciful actions to intervene in these circumstances.

But are those the defined limits of our engagement? Is there more we should do to safeguard animals, especially in environments we’ve altered so consequentially?

During the many months when the Penelope and the other deer dominated Bochner’s thinking, never did he make a call to a wildlife veterinarian or seek counsel or assistance from a wildlife rehabilitator. The deer were free; they chose to interact with him and treat him like a friend. If anyone was confined, it was Bochner, who seemed contained by an invisible fence, a mental electrical impulse halting his movements at his property line, even as the deer roamed more widely.

Bochner models human responsibility, but there’s no call for us to replicate his action. His rapport with Penelope is sui generis and all his own. But he does share plenty of insights and reminds us that there is much more than meets the eye to the often-maligned deer. His book also doubles as a sort of ethnographic account, bestowing names to the members of this deer community and describing their surprising expressions of empathy, playfulness, grief, and even malice.

This is a story with more than its share of pathos. Try as he might to fend off the harsher realities of nature, and the human hazards that surround the deer, he could not offset or mitigate all threats. There is pain and misery in this world, and it comes from so many directions. The wider the circle of moral concern, the more pain and death to confront.

The presence of pain and death in the world should never cause us to throw up our hands. Bochner understands that. And his journey reminds us he made a difference in the world, making their well-being the priority in his life. Penelope did not succumb to starvation or a trampling by her mother because of him. She lived into adulthood and came to recognize and experience care and kindness because of him. With life and freedom, she even became a mother, producing at least two sets of fawns. For a creature who received not a bit of love from her mother at the onset of her existence, she later found love.

I am sure, for all the emotional pain and sacrifice that’s paired with love, he didn’t regret going down this path for even a moment. He saw a fragile life and he came to protect that life. It was a rare kinship that developed, the bond as magnetic force. He came to understand that Penelope was somebody special, with her own desires and challenges and joys. He increased her quotient of joy. And that was enough.

The book is available through Amazon here and other booksellers.

Wayne Pacelle, author of “The Bond” and “The Humane Economy,” both New York Times bestsellers, is president of Animal Wellness Action and the Center for a Humane Economy.