Global Cockfighting and Its Role in the American Border Crisis

The FIGHT Act is one major remedy for rampant animal fighting and the cluster crimes commingled with it.

- Wayne Pacelle

You can listen to this article here:

Cockfighting is a multi-billion global crime network, with U.S.-based cockfighters at the center of the whole enterprise, feeding birds to fighting arenas in our homeland and around the world. Mexico and the Philippines are America’s biggest partners in this illicit trade, and American cockfighters are consorting with clans involved in murder, kidnapping, narcotics trafficking, money laundering, bribery, and more.

The Fighting Inhumane Gambling and High-Risk Trafficking (FIGHT) Act is our latest legislative maneuver to dismantle this crime business. Last week, we gained a great partner with the National Sheriffs’ Association (NSA). In endorsing the FIGHT Act, the association, on behalf of more than 3,000 elected sheriffs nationwide, “acknowledges animal fighting is a crime of violence” with “links to crimes against people including, but not limited to, child abuse, murder, assault, theft, intimidation of neighbors and witnesses, and human trafficking.”

The NSA joins the National District Attorneys Association, the American Gaming Association, the United Egg Producers, and more than 600 other agencies and organizations in backing H.R. 2742 by Reps. Don Bacon, R-Neb., and Andrea Salinas, D-Ore., and S. 1529 by Sens. Cory Booker, D-N.J., and John Kennedy, R-La.

“Animal fighting is vicious animal cruelty at its core, but we in law enforcement know it’s tangled up with illegal firearms, drugs, gambling, and outbursts of violence,” said Sheriff Greg Champagne, president of the National Sheriffs’ Association and the St. Charles Parish Sheriff in Louisiana. “It is a priority for the National Sheriffs’ Association to get the FIGHT Act over the finish line in Congress this year. Dogfighting and cockfighting undermine public safety in our communities, and there’s no time to waste in strengthening our laws.”

A Cockfighting Epidemic, with U.S. at the Center

From Cocke County, Tenn., to Verbena, Ala., to Eugene, Ore., animal fighting busts have uncovered so much more than evidence of staged cruelty. Many of the U.S. cockfighters provide birds for fighting pits in our homeland but also to far-flung outposts throughout the world. One of our investigations revealed that cockfighters based on the U.S. mainland — with Oklahoma cockfighters at the center of it all — sent at least 11,648 fighting birds to Guam between 2016-2021.

“While we have backyard birds on Guam that families raise for eggs or meat, these thousands of fighting roosters are useless for either,” said retired Army Colonel Tom Pool, the former Territorial Veterinarian for Guam and now senior veterinarian with Animal Wellness Action.

“There is simply no other rationale for the shipment of very expensive adult roosters to our island but for cockfighting. We know that the people on both ends of these transactions have been involved in the criminal practice of cockfighting. Animal fighters stage gladiator-type events that result in the maiming and destruction of innocent animals forced into the enterprise for the thrill of bloodletting and illegal gambling,” he said.

It’s a far larger enterprise in Puerto Rico, whose political leaders and cockfighting pit operators failed as they tried maneuvers in our federal courts to invalidate the 2018 federal law applying the prohibitions in the national anti-animal fighting law to the U.S. territories, including 100 fighting arenas on the island.

Club Gallístico of Isle Verde in San Juan is one of dozens of arenas in the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico. In fact, when you fly into the San Juan airport, you can’t miss a large arena with “Live Cockfights” emblazoned in neon on the facade. The blaring sign may draw the curious, but most attendees are seasoned practitioners of cockfighting.

U.S. District Court Judge Gustavo Gelpí, a Puerto Rico native, shot down Club Gallístico’s claims: “[N]either the Commonwealth’s political statues, nor the Territorial Clause, impede the United States Government from enacting laws that apply to all citizens of this Nation alike, whether as a state or territory.”

Puerto Rico’s cockfighters and politicians also lost in the federal appeals court, but they continue to defy the law. Soon after taking office, Gov. Pedro Pierluisi stated that he is “committed to supporting an industry that generates jobs and income for our economy, that represents our culture and our history.” He declared that he and Jennifer González-Colón, Puerto Rico’s Resident Commissioner in Congress, “will continue to fight for them.”

Since Congress clarified the federal law, our federal law enforcement agencies have yet to make a single arrest and have not shut down a single animal fighting pit, even as cockfighting venues openly advertise and conduct their fighting derbies. This is a disgrace. It is not the Commonwealth’s prerogative to opt out of this U.S. law. And whether Puerto Rico is a state or a territory, the outcome when it comes to cockfighting is the same: it is illegal. The federal courts have declared that to be the circumstance, over and over again.

It’s the presence of these cockfighting havens that enables the U.S.-based industry to thrive. A Philippines-based television network in 2020 released 50 videos showing two hosts making visits to U.S.-based cockfighting complexes, where the American cockfighters touted the bloodlines of their fighting birds, with some of the animals destined for big global events such as the “World Slasher Derby” in Manilla. One Alabama-based cockfighting operator told the Filipino television broadcaster that he sells 6,000 birds a year to Mexico alone for as much as $2,000 a bird, generating millions in illegal sales.

In 2022, there was $13.7 billion wagered on cockfights conducted in the Philippines. Even as cockfighting generated billions in online gaming in his country, former Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte issued a temporary ban on online betting at cockfights after dozens of people were kidnapped and never heard from again in the country. One woman, who had unpaid gambling debts accrued through online cockfights, reportedly sold her child to pay off her debts.

America’s Border Crisis

Cockfighting is a little understood feature of the border crisis in America. It’s a criminal form of trafficking. It involves scores of individual victims crossing the Rio Grande. It is a public safety threat and a massive expense to American taxpayers.

Cockfighting is outlawed in every state in the United States, and it is a felony in Texas. But south of the border, it is legal, and U.S. cockfighters smuggle hundreds of thousands of fighting birds to cartel-controlled cockfighting arenas in Mexico for regular bloodletting, high-stakes gambling, and money laundering. The flow of birds also moves in the opposite direction, with the cartels shipping fighting birds along north-facing routes to their network of criminal operators in our homeland.

All we need is to check the court dockets in Texas counties to understand it’s an epidemic.

Recently, Bexar County law enforcement arrested 47 people and seized 200 birds, along with illegal weapons. A raid in Goliad County resulted in 60 arrests and several illegal weapons seized.

Earlier this year, more than 160 roosters were seized in a Potter County bust where according to the sheriff, “many” participants were “unlawfully in the United States.” At a cockfight busted by the San Jacinto Sheriff, suspects were “expected to face multiple felony charges, ranging from animal cruelty, cockfighting, illegal gambling, unlawful weapon possession, organized crime, and federal firearm possession by illegal immigrants.”

We saw more of the same in Cherokee, where two dozen suspected cockfighters were arrested on similar charges. And in Lynn County, the sheriff brought felony charges “because of organized criminal activity.”

There have been a series of interdictions at the border, including a federal enforcement action where officers “made an unusual discovery, roosters deeply hidden within passenger vehicles.”

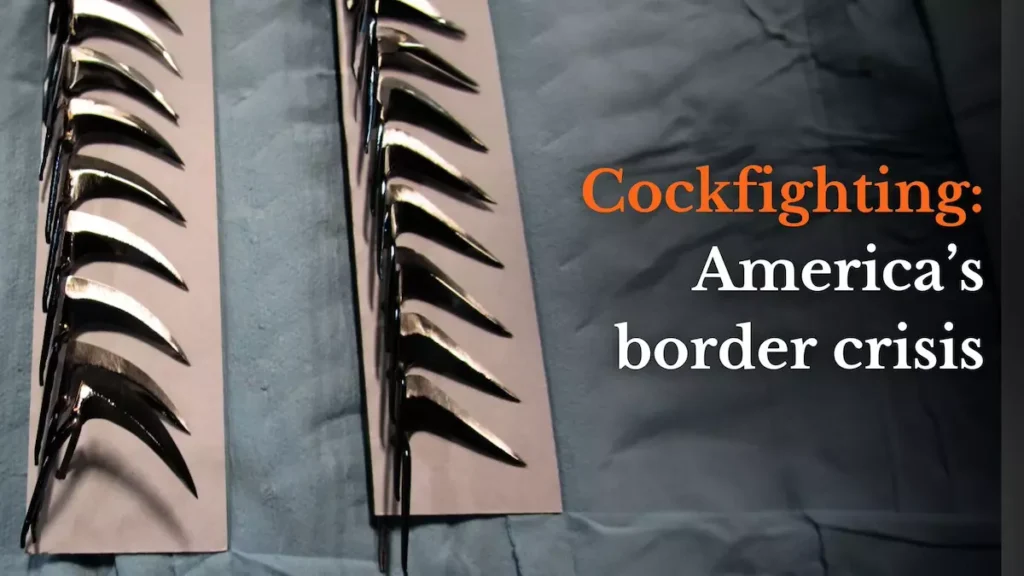

This is no benign trade. First, cockfighting is barbaric and cruel. Fighting birds are fitted with razor-sharp blades on their legs to hack and cut each other for the sick enjoyment of spectators who get a thrill from the bloodletting. But apart from this sheer barbarism, cockfights also are a gathering place where organized crime festers and spills over into communities.

In Hidalgo County, Texas, in early June, a young man shot his uncle in a dispute over birds thought to be raised for cockfighting. There was also a shooting at a Dallas cockfight last year.

And the cockfighting-related violence in Mexico is chilling in its scale. In 2022, in the Mexican state of Michoacán, cartel members entered a cockfighting arena, sealed off exit routes, and shot and killed 20 people. Three of the victims were Americans, including a mother of four from Illinois. A similar incident occurred at a cockfighting derby in Guerrero in January 2024, where 14 people were wounded and six murdered, including a 16-year-old boy from Washington state.

Cockfighting has also been linked to outbreaks of bird flu (H5N1) in Asia, and there have been 15 outbreaks of another kind of bird flu, virulent Newcastle Disease, in the United States in recent decades. Ten of those 15 outbreaks were linked to fighting birds smuggled across the border from Mexico. The United States indemnifies the farmers and has paid out billions of your tax dollars to reimburse them for birds lost to disease.

Texas is at a crossroads of the North American cockfighting trade. Three neighboring states — Louisiana, New Mexico, and Oklahoma — were the last ones to criminalize cockfighting. Organized criminal networks of cockfighters still operate, coordinating with associates in Texas and Mexico and contributing to the crime wave.

This is one feature of the border crisis we cannot ignore.

The FIGHT Act will do so much to curb this crime wave. H.R. 2742 and S. 1529 would ban online gambling on animal fights, allow courts to seize fighting pits and other property used by convicted animal fighters in the commission of their crimes, stop the shipment of fighting roosters through the mail, and allow law-abiding citizens to protect their homes and families by bringing civil suits against cockfighters and dogfighters when governmental authorities are too slow to act.

With a law like the FIGHT Act to protect the public from deadly cross-border crimes, we can finally put the tools into the hands of law enforcement to wipe out animal fighting in the United States and halt the spillover of our cockfighting activities to other nations throughout the world.

Will you take action by writing to your elected representatives in support of the FIGHT Act today?

Wayne Pacelle is president of Animal Wellness Action and the Center for a Humane Economy. He is the author of two New York Times bestselling books about the human relationship with animals.

Dear reader: If you support substantive policy work to protect animals, please consider donating to Animal Wellness Action today. You can give any amount one time, or make it a monthly gift, as many of our supporters do. Thank you for helping us fight for all animals. Please go here to make your contribution.