An Animal Wellness Action Investigation

Investigators Unpack Cockfighting Trade That Spans from Mid-America to Manila

Bright lights. Corporate sponsors. And at the center — animals forced to kill each other.

I stood surrounded by 10,000 spectators — almost all men — shouting and gesturing wildly inside a packed coliseum in Manila. On a raised dirt platform six men were preparing for the next fight. On opposite sides of the brightly lit platform, two handlers thrust muddy white roosters toward each other, nearly smashing their heads together. Above them, an enormous jumbotron featuring a Dairy Queen ad threw more light on the spectacle below. Even though I’ve long documented organized animal cruelty, I had never seen animal fighting this normalized — or this celebrated.

The World Slasher Cup (WSC) — billed by the Philippine cockfighting tabloids as the “Olympics of cockfighting” — was in high gear at the Smart Araneta Coliseum in Manila. Most entrants were Filipinos but men from other Southeast Asian nations were represented among the 300-plus cockfighting entrants participating. The largest foreign contingent was from the United States — cockfighting traffickers, including Jeff Hudspeth of North Carolina and Dan Miller of Oklahoma, well known to Animal Wellness Action for their disregard of U.S. laws against staged animal fighting.

I watched hundreds of fights and recorded it all. One match featured Dan Miller of the Miller Time Game Farm near Antlers, Oklahoma, and Firebird Angels, owned by Biboy Enriquez of the Philippines. Miller and Enriquez drop their birds into chalked circles in the dirt and back away to opposite corners of the glass-walled pit to watch. The two white roosters approach each other with studied indifference — then with lightning speed, one leaps and drives its blade deep into the other.

Within a minute both birds’ white feathers are soaked in blood. The pit is littered with feathers. They are struggling to stand. A referee grabs them by their wings, forces them beak-to-beak and drops them again. They collapse instantly. The referee repeats this eight times before they sputter and go still.

The Smart Araneta Coliseum in Manila, which hosts the World Slasher Cup (WSC) — billed by the Philippine cockfighting tabloids as the “Olympics of cockfighting.”

The referee picks up the mangled birds, turns them upside down and hands them to handlers who remove the knives and carry them out of the pit trying not to get blood on the floor of the arena. The owners have already left the pit. Gamblers in the audience are tossing money back and forth to settle bets.

Billions Wagered on Cockfights in Borderless Global Crime Racket Tethered to U.S.

What looks like a local spectacle is powered by an international pipeline — with American breeders, U.S. brokers, and commercial airlines helping move fighting birds into the Philippines despite U.S. law forbidding that illicit commerce. American fighting roosters from a famous bloodline are highly prized in the Philippines and “sabungeros” (cockfight enthusiasts) will pay up to $5,000 for a trio (one gamecock + two hens). Many of the Filipinos were fighting their prized American roosters at the WSC.

Korean Air and other carriers with flights originating in the U.S. charge a modest fee to enable the cockfighters to pit their birds in Manila and other major cockfighting capitals in southeast Asia. The Animal Welfare Act (7 U.S.C. § 2156) makes it illegal to ship animals for fighting but the cockfighters engage in an elaborate ruse to sidestep federal authorities who’ve long ignored the problem and failed to enforce the rule of law. Shipments are labeled “breeding fowl.” We found there is no legitimate trade in adult roosters from North America to Asia.

The staged animal battles deliver the violence that the participants crave. The fights begin with the animal handlers doping the birds to excite them and then agitating them in the pit by putting them beak to beak and stoking their aggressive instincts, amplified by steroids, ketamine, and a brew of other drugs. Gaffers tie 4-inch-long knives to the left leg of each rooster and return them to their owners.

Within the last two years, it came to light that at least 34 — and possibly more than 100 cockfighting participants disappeared in 2021, either while traveling to fights or working within the trade. Their bodies were found dumped in Taal Lake near Manila. Last year, Philippine law enforcement charged e-sabong kingpin Charlie “Atong” Ang with the murders. He is currently wanted by Interpol.

The violence is fueled by high-stakes gambling. Cockfighting is a multibillion-dollar industry in the Philippines — an industry that embraces the American-bred birds and the men who travel across the world to fight and sell them. The rise of e-sabong, or online gambling on cockfights, during the COVID-19 pandemic, created a $3.5 to $5.3 billion industry overnight.

E-sabong platforms recorded as many as 100,000-plus gamblers online at a time. Gambling addiction quickly led to social problems and former President Rodrigo Duterte banned e-sabong. But the men involved are not law-abiding people, and as soon as the police shut down one platform, it seemed that a new one popped up elsewhere, in an elaborate game of whack-a-mole. Murder and mayhem were the outgrowth of this above-ground, below-ground enterprise centered around the thrill of staged animal combat.

Internet gambling on cockfights in the Philippines is now a global pandemic. Social media used by cockfighters and gamblers in the United States are awash in English-language e-sabong ads. American gamblers and cockfighters are hooked. They can watch and wager from their mobile phones 24/7. An unknown number of U.S. dollars have been transferred from the United States to e-sabong criminal networks in the Philippines. While the U.S. contribution amounts are not known, estimates for the total global wager volume are $13 billion annually.

Tracing the U.S.–to–Manila Smuggling Route

Animal Wellness Action investigators were recently able to trace the illicit traffic from gamefowl farms in states such as Oklahoma, Texas and Mississippi to brokers such as North Texas Livestock Shipping (NTLS) in Dallas. NTLS ships the birds on Korean Air to Manila Airport via Incheon Airport in Korea. Other fighting rooster brokers operate from Georgia to California. There are tens of thousands of birds moved annually from the United States to the Philippines for fights, and that means illicit commerce in the tens of millions. We estimate that birds are trafficked to an additional two dozen countries, most of them south of the U.S. border in Latin America and to other Asian nations in addition to the Philippines.

U.S. airlines do not accept live birds for shipment to the Philippines, but Korean Air, Philippine Airlines and Cathay Pacific reportedly do. Filipino cockfighters and breeders exhibiting at the World Gamefowl Expo in Manila, just prior to the WSC, told Animal Wellness Action that Korean Air was its go-to source for shipments originating in the New World. Freight forwarders in the Philippines told our investigators the same thing. Korean Air uses both cargo planes and passenger planes to ship birds to the Philippines. It is unlikely that Korean Air passengers are aware that in the cargo hold below them may be American fighting roosters destined for cockpits in the Philippines.

With this illicit trade and organized crime network in mind, former Fort Bend County Sheriff and Congressman Troy Nehls, R-Texas, along with more than a dozen other U.S. lawmakers, have introduced federal legislation to fortify our national law against animal fighting and cut off the illegal smuggling of fighting animals. H.R. 7371, the No Flight, No Fight Act, comes just as investigators are tracking the movements of U.S. cockfighters and their birds to the Philippines for the World Slasher Cup.

Rep. Nehls is the chairman of the Subcommittee on Aviation, which is part of the larger House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. He’s already attracted a broad set of cosponsors including Vern Buchanan, R-Fla.; Salud Carbajal, D-Calif.; Troy Carter, D-La.; Juan Ciscomani, R-Ariz.; Brian Fitzpatrick, R-Pa.; Lance Gooden, R-Texas; Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif.; Chris Pappas, D-N.H.; Christopher Smith, R-N.J.; Dina Titus, D-Nev.; and Jefferson Van Drew, R-N.J.

“Airlines should not be serving as cargo carriers for animal fighters and other illegal operators, and this bill finally provides plain-language standards to direct air carriers to stop these transports on the front end,” said Wayne Pacelle, president of Animal Wellness Action and the Center for a Humane Economy. “This is organized crime, rivaling the drug trade and the illegal wildlife trade in scale. It stinks of animal cruelty, murder, illegal gambling, narcotics trafficking, and other mayhem and lawlessness.”

The No Flight, No Fight Act is a complement to the FIGHT Act, H.R. 3946, introduced by Reps. Don Bacon, R-Neb., and Andrea Salinas, D-Ore., and S. 1454, led by Sens. John Kennedy, R-La., and Cory Booker, D-N.J. The FIGHT Act would amend the Animal Welfare Act to strengthen federal enforcement by:

- Prohibiting both in-person and online gambling on animal fights

- Banning shipment of mature roosters through the U.S. mail

- Authorizing citizen suits against sponsors and participants

- Enabling forfeiture of animals and property used in animal-fighting crimes

The FIGHT Act already has a broad coalition of about 1,100 agencies and organizational endorsers. Law enforcement agencies and prosecutors are increasingly stepping up, aided by the investigations of Animal Wellness Action, the Center for a Humane Economy and Showing Animals Respect and Kindness (SHARK). Key egg and poultry trade associations panicked about losses of their birds from avian diseases spread by gamefowl.

Cockfighting and the Threat of Avian Disease

“As a veterinarian, I can tell you that cockfighting is a near-perfect storm for spreading H5N1 avian influenza,” noted Jim Keen, DVM, PhD, the director of veterinary science for the Center for a Humane Economy who has deployed to contain zoonotic disease outbreaks across the world, including avian flu outbreaks in the United States. “Fighting cocks from multiple source farms going to and from fighting pits are often transported across state or international lines, crowded in close quarters, stressed, injured, and shed copious respiratory secretions and blood.”

Keen described that H5N1 (“bird flu”) first emerged in China as small-scale contained poultry and human outbreaks in 1997 likely from a wild waterfowl. The virus then re-emerged in 2003-2004 and became widespread, unconstrained, and endemic throughout southeast Asia, with cockfighters in Thailand playing a major role in the disease’s spread. Since then, the virus has spread globally resulting in the deaths of more than 500 million poultry, millions of wild birds, and countless wild mammals.

“Cockfighting activity was documented as a major risk factor both in the spread of H5N1 among backyard and commercial flocks in Southeast Asia, but also in the spillover from poultry to people,” added Keen. “Almost all roughly 900 confirmed human H5N1 cases worldwide, including more than 400 human deaths, have involved close human contact with poultry. In southeast Asia, many human cases were cockfighters.”

The former USDA veterinarian and epidemiologist said that cockfighting activity in the U.S. has “almost certainly been an important factor in the epidemic spread of bird flu H5N1 since January 2022 across our commercial poultry industry and backyard flocks in all 50 states.” He warns that “if cockfighting birds are infected, they have the potential to expand the geography and duration of viral outbreaks throughout the U.S. and the world.” Dr. Keen’s comprehensive report on cockfighting and avian diseases can be found here.

Six Days of Continuous Bloodletting

At the fighting venue, staged animal fights at the World Slasher Cup started at noon and went straight through to near midnight every day for the six-day event. We counted more than 800 fights, in a running spectacle that might have rivaled the bloodletting in the era of the Roman Empire and the spectacles on display at the Colosseum. The carnage was relentless but the spectators and cockfighters never seemed to tire. The line of cockfighters holding their birds to fight was so long it disappeared into the dark of the tunnel.

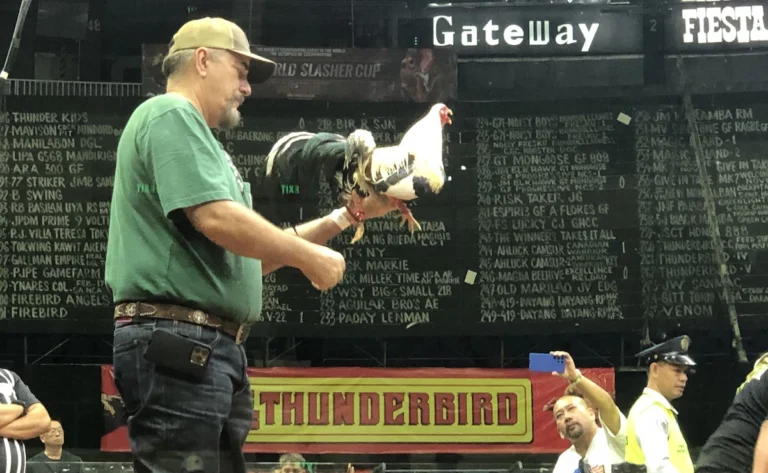

Dan Miller of Oklahoma preparing his bird for battle. A bird he undoubtedly boxed up to ship to the Philippines, breaking federal laws.

On the final day of the WSC the finalists were announced. Winning breeders received their trophies and photo ops flanked by Filipino beauty queens. Breeders, including American breeders, do get large cash prizes but they compete first and foremost for significant financial benefits in the form of the sales value of winning birds. Winning the World Slasher Cup functions like a Michelin star for fighting-rooster breeders — it instantly multiplies the commercial value of their bloodlines. Their bird prices jump dramatically with a stag or pullet selling for two to ten times more. Just as in the real Olympics, sponsorships come from feed companies and supplement and drug brands. American winners immediately realize increased sales to Guam, Mexico, Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

Troy Thompson (Oklahoma), Dan Miller (Oklahoma), Nathan Jumper (Mississippi), Jeff Hudspeth (North Carolina), and Chris Copas (Kentucky) had undoubtedly boxed up their birds to ship to the Philippines, breaking federal laws and planning on selling their birds for the fights to soon come. Indeed, the American cockfighters sold out their stock of birds within hours of the opening of the World Gamefowl Expo. Their collective work confirmed that the United States had cemented its status as the cockfighting breeding ground for the world.

It’s customary for American gamefowl breeders, including the men named above, to claim no involvement in illegal cockfighting. Just about every farm has a sign proclaiming that “no fowl are sold for illegal purposes.” These are distinct breeds of birds — asils, hatches, sweaters and kelsos — the aggressive breeds most popular with cockfighters and as different from laying hens and meat birds as King Charles Cavalier spaniels are from Doberman Pinschers or Rottweilers. To the public they claim their fields full of tethered birds are destined for the minuscule, largely fictionalized poultry exhibition market. Yet no hobbyist poultry exhibitor is going to pay the $3,000 that breeders ask for a winning rooster, nor is there any money in poultry shows that would enable the breeders to pay thousands of dollars to fly their birds to foreign markets across the globe.

When breeders speak to potential buyers through one of several Filipino TV stations or influencers specializing in cockfighting, they typically tout their bird’s “gameness” or “cutting ability” — code for cockfighting prowess. Ultimately, the charade is exposed as a fraud when these same breeders and brokers show up in Manila every January to take to the pit to prove their bird’s winning bloodline.

Some 1,500 miles to the east of Manila lies Guam — a territory of the U.S. Records from the Guam Department of Agriculture show that nearly 12,000 adult roosters were shipped from the U.S. mainland to Guam in under five years, despite the island having no commercial poultry industry to justify such imports. Cockfighting is conducted openly there, though it is a federal crime that authorities have not enforced locally. The former Territorial Veterinarian, Dr. Tom Pool, who refused to approve the rooster permits during his 17-year tenure, stated that there is no legitimate agricultural reason to transport adult roosters such a distance, making cockfighting the only plausible purpose. “The wanton cruelty behind this inconvenient truth that authorities and airlines are turning a blind eye to needs to be stopped and both the FIGHT Act and the No Flight, No Fight Act are critical to halting this smuggling and illegal trafficking of fighting animals,” said Dr. Pool.

For too long, American gamefowl breeders, airlines and brokers have been able to flout our laws against cockfighting and profit from the cruelty and criminal gambling networks on an international scale. If Congress takes up and passes The FIGHT Act and the No Flight, No Fight Act, law enforcement will have even more tools to address this deadly trade built around animal exploitation and other forms of organized crime.

The author of this piece will remain anonymous for his safety.

Take Action Now: Contact your legislators and urge passage of both the FIGHT Act, H.R. 3946 and S. 1454 and the No Flight, No Fight Act, H.R. 7371.