The Lethal Loophole in America’s Poison Laws

How online rodent-killer sales are killing America’s wildlife

by Ted Williams

Dr. Maureen Murray of Tufts Wildlife Clinic in North Grafton, Massachusetts, was trying and failing to maintain a clinical countenance. She was clicking through X-rays from necropsies she’d done on raptors killed by second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs), and the images were depressing both of us.

These poisons are lethal to rodents because they prevent blood from clotting by inhibiting the function of Vitamin K, thereby causing fatal bleeding. SGARs are also lethal to all manner of nontarget wildlife. When rodents ingest these poisons — even when deployed by professional exterminators inside a seemingly sealed building — they inevitably exit and stagger around in the open for up to five days, displaying themselves as tempting prey.

Nontarget victims of secondary poisoning include, but are not limited to, raptors, endangered Mexican wolves, endangered northern gray wolves, endangered San Joaquin kit foxes, imperiled swift foxes, red foxes, gray foxes, coyotes, raccoons, opossums, black bears, skunks, badgers, fishers, martens, minks, weasels, otters, mountain lions, bobcats, and pet dogs and cats.

Like DDT, SGARs bioaccumulate in nontarget wildlife. Victims don’t have enough red blood cells to deliver oxygen to their tissues, so they’re lethargic. They stumble. Their heads droop. At best, they’re compromised, which in the wild is a death sentence. At worst, they bleed from their eyes, ears, noses, mouths and internal organs. Ruptured blood vessels frequently cause eyeballs to explode.

In 2020, Murray — like her colleagues, both a scientist and an advocate — reported in the journal Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry that 100% of red-tailed hawks admitted to the clinic have ingested anticoagulant rodenticides, mostly brodifacoum and bromadiolone.

Each image Murray projected seemed sadder than the last. There was a great horned owl with a hematoma running the length of its left wing; a red-tailed hawk’s entire body cavity glistened with unclotted blood. Another red-tail had a hematoma that had ballooned its left eye to 10 times normal size. Dozens of raptors had pools of blood under their skin. Maybe the saddest image was that of the red-tail still containing an egg. Blood vessels around her oviducts had ruptured, and she’d slowly bled to death from the inside.

For many raptors, SGAR poisoning is doubly debilitating because they’ve already ingested toxic fragments of lead bullets left in gut piles or unretrieved game. A study published in the February 17, 2022, issue of Science found that “almost half” of all bald and golden eagles sampled “had chronic, toxic levels of lead” that appeared “high enough to suppress population growth in both species.”

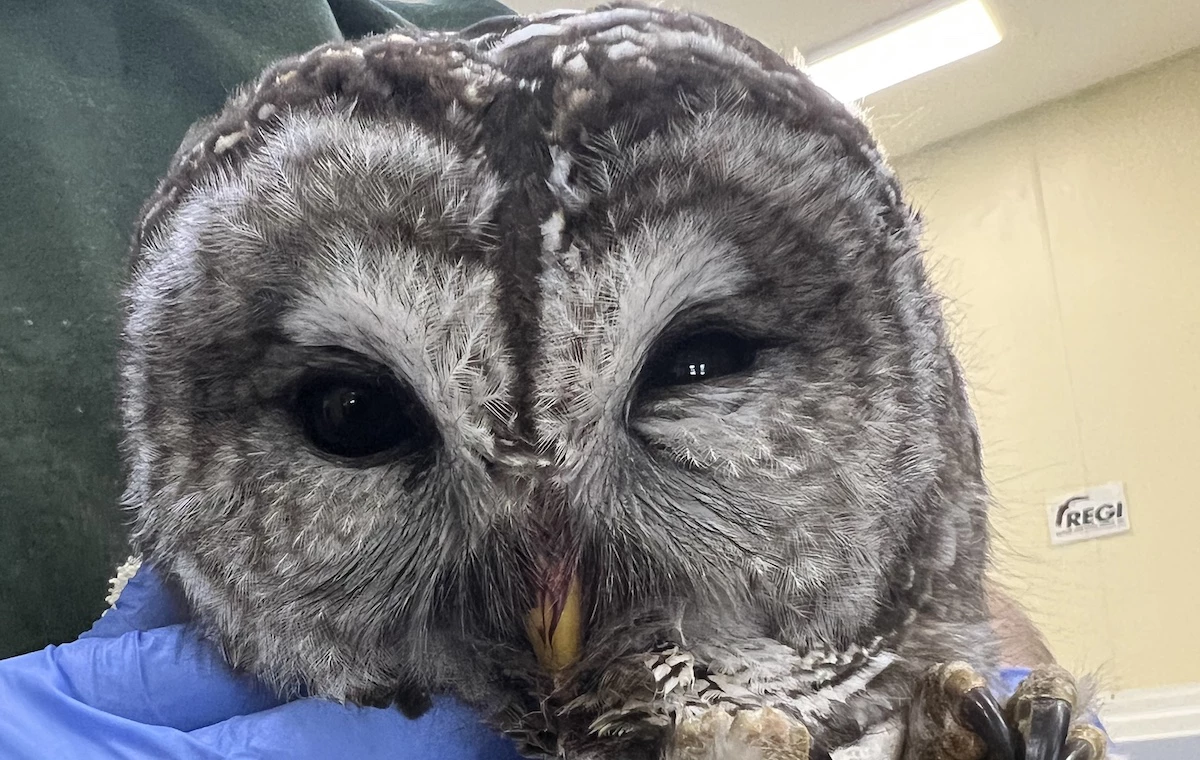

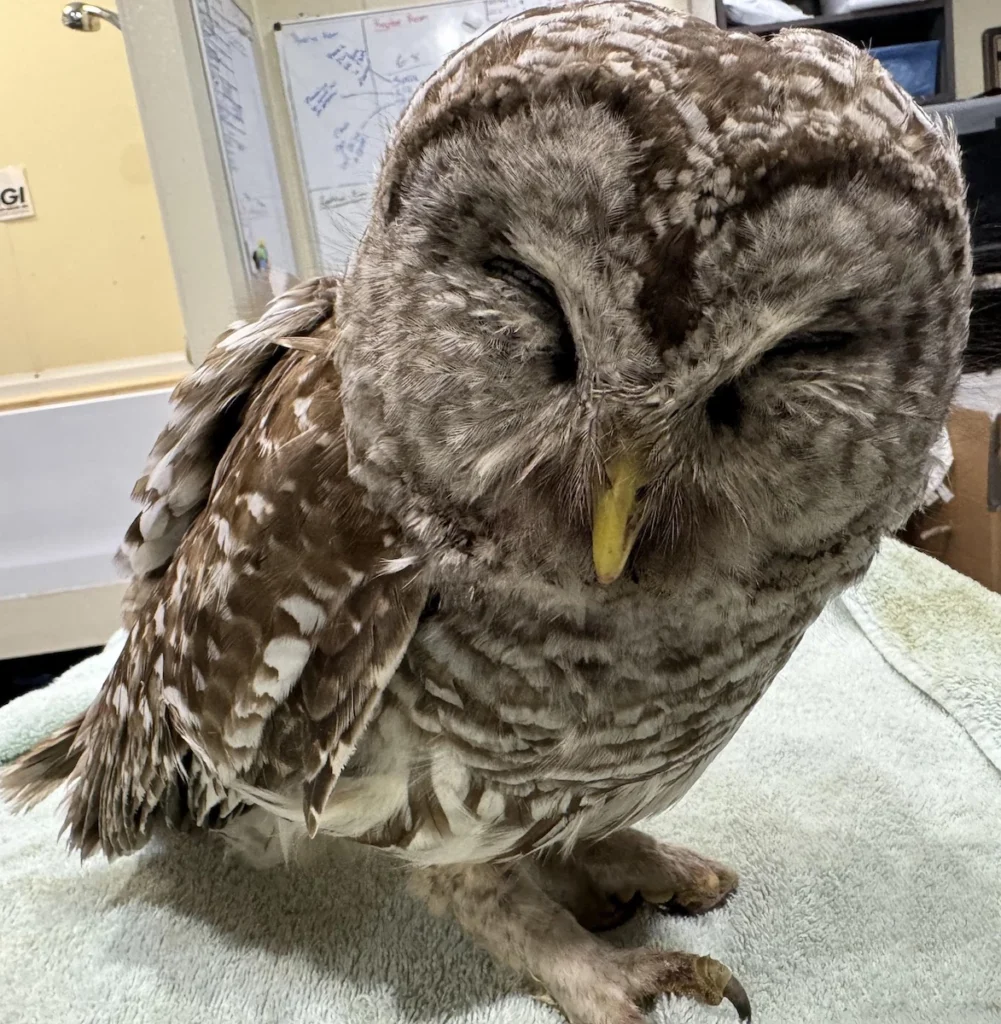

“We get lots of raptors in. Adult birds eat [SGAR-poisoned] mice and bring them to their babies,” said Marge Gibson, the founder and director of Antigo, a Wisconsin-based Raptor Education Group that rehabilitates injured and orphaned native birds and educates the public about wildlife issues. “People find them [adults and nestlings] when they die and fall from the nests. We see this often. It is so disheartening. These chemical companies have excellent marketing, which is misleading at best.”

The poisoning leads to gory eye trauma where the raptors’ eyes burst from internal bleeding. The pooled blood attracts maggots, which subsequently travel into the birds’ brains and cause death. “For some reason, it’s almost always the left eye that bursts,” Gibson said. “We’re seeing more of that this year. Maggots get in through the ears, too. We had a great-horned owl that had blood leaking from her ears. They were full of maggots.”

Advent of SGARs

First-generation “multi-dose” anticoagulant rodenticides were developed in the late 1940s and 1950s. Warfarin, for example, proved more effective as a human blood thinner, and is still prescribed as such. Because the first dose sometimes caused only sickness, rodents often learned to avoid a second dose that would have killed them.

So, in the 1970s, at the request of the World Health Organization, Imperial Chemical Industries of London developed “single dose” SGARs. Today, SGARs used in the United States are brodifacoum, bromadiolone, difenacoum, and difethialone.

On the mainland there is no SGAR delivery system or place of application that is safe for wildlife. Still, the EPA allows farmers and exterminators to buy and apply SGARs. It has banned public sale at “consumer stores, including drug stores, grocery stores, hardware stores, club stores, and similar retail outlets.” Apparently, the EPA hasn’t heard of the internet. When I Googled “second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides,” the screen lit up with purchase opportunities.

Among online purchasers of SGARs, there’s scant understanding of how these biocides endanger nontarget wildlife, pets, and young children — and maybe little concern, given the public hatred of nonnative rats and mice. They displace and kill our native wildlife. They contaminate our food. They spread diseases. America’s common conviction is that if a little poison kills, a lot kills better.

Prevalence

Liver analysis of 104 necropsied common buzzards and 190 common kestrels across the Iberian Peninsula and its archipelagos turned up SGARs (mostly brodifacoum and bromadiolone) in 81.7 percent of the buzzards and 84.7 percent of the kestrels.

Five SGARs — brodifacoum, bromadiolone, difethialone, difenacoum and flocoumafen — are still registered for public use in Australia. Potentially fatal concentrations of SGARs were found in 15 percent of endangered Tasmanian devils, 20 percent of endangered eastern quolls, 22 percent of “near-threatened” western quolls and 20 percent of endangered spotted-tailed quolls. SGARs were also detected in endangered Tasmanian wedge-tailed eagles, endangered Tasmanian masked owls, “vulnerable” powerful owls and endangered Carnaby’s black cockatoos.

In a U.S. study, SGARs (mostly brodifacoum and bromadiolone) were found in the livers of 83 percent of 96 bald eagles and 77 percent of 13 golden eagles.

In California, 16 raptor species studied contained rodenticides (mostly SGARs), including 82 percent of the Cooper’s hawks, 72 percent of the red-tailed hawks, and 59 percent of the barn owls. SGARs were also found in 100 percent of the mountain lions, 82 percent of the coyotes and 69 percent of the endangered San Joaquin kit foxes. Sublethal SGAR retention was linked to severe, sometimes fatal, mange in mountain lions and bobcats, as well as to immune system suppression in bobcats. (In 2021, California became the first state to ban sale and use of SGARs, save for rat infestations that threaten public health.)

SGARs harm humans, too. Each year, about 10,000 kids, almost all under age three, swallow SGAR pellets. Children of impoverished minority families are disproportionately affected. A New York study found that 57 percent of children hospitalized for consuming SGARs were Black, 26 percent Latino.

Horror Stories

Jeannine Altmeyer is a famous opera singer who has gained world recognition for her Wagner and Strauss roles. Her portrayal of Brünnhilde in the Grammy-winning recording of “The Ring Cycle” is hailed as a standout moment in opera history.

Because Altmeyer’s 2.5-acre property in Ojai, California, is surrounded by orange and avocado farms, she had a major rat infestation. So she hired a professional exterminator company. “These guys came every month for three years,” she told me. “There were far fewer rats for the first two years, but one winter we had a horrible infestation. Every night I’d see at least five rats crawling on the chicken coop. The company put out these tamper-proof [bait] boxes. Then my beautiful 5-year old golden retriever, Franz, was acting strange. His gums were snow white. Back then, I didn’t know what that meant. He weighed 90 pounds. We had to carry him downstairs on a sheet, and he died on the way to the vet’s. Franz was a wonderful dog. I had a necropsy done. They found brodifacoum.”

Altmeyer paused to collect herself, then continued, her voice cracking. “The pest-control people told me the bait wasn’t dangerous, that there was no secondary poisoning. I used to throw the dead rats over the wall. I would never do that now. The local vets see lots of poisoned dogs because the farmers indiscriminately put the stuff out in their orchards. One woman didn’t have the money to pay for treatment for her poisoned dog, so she was going to sell her washer and drier. The vet had to tell her, ‘Keep your machines; I can’t save your dog.’”

Last year, a pair of great horned owls, affectionately known as the “rockstars of the neighborhood,” nested in Chicago’s Lincoln Park — this to the delight of visitors who didn’t need binoculars to admire them and who joyfully celebrated the hatching of an owlet in late winter.

Then the owls started dying. In early April “Papa Owl,” as he was called, expired. The owlet died in March. Finally, in May, the carcass of Papa Owl’s mate, “Mama Owl,” was found on a sidewalk. Necropsies revealed that she, Papa Owl, and their owlet had been fatally poisoned by multiple SGARs.

“The most famous red-tailed hawk in the world,” according to New York City media, was 22-year-old “Pale Male.” For years, he and successive mates nested on the decorative window pediment of a building facing Central Park, making it a prime viewing spot for birders who gathered every spring with binoculars and scopes at the Model Boat Pond.

In February 2012, Pale Male’s mate, Lima, turned up dead shortly before she would have laid eggs. The inside of her mouth was pallid, as were her heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, and brain. Fatal doses of three SGARs, including brodifacoum, were found in her liver.

Pale Male then took his sixth mate — “Zena.” The pair fledged three chicks, one of which is believed to have been fatally poisoned by SGARs and two of which were gravely sickened by SGARs, treated with Vitamin K, and released. Pale Male died, presumably from SGARs found in his liver. The fates of Zena and the two released chicks are unknown.

If wildlife advocates are to succeed in reducing SGAR pollution, they need to choose battles they can win — certainly local, state, or national regulations that prohibit online sales to the general public and perhaps even limiting use by exterminators outside rat-infested communities.

Picking the Right Fights

If wildlife advocates are to succeed in reducing SGAR pollution, they need to choose battles they can win — certainly local, state, or national regulations that prohibit online sales to the general public and perhaps even limiting use by exterminators outside rat-infested communities.

When Golden Gate Bird Alliance director, Glenn Phillips, was directing the New York City Audubon Society, birders scolded him and his organization for advocating only a ban on public use of SGARs while giving professional exterminators a pass.

At the time, Phillips told me this: “Our city has a huge rat problem. We can’t ban all use of rodenticides. It’s never going to happen. If we were to advocate that, we couldn’t get the support of a single city agency. If you want to tilt at windmills, you can try. If you want to actually make things better for birds, you have to do what you can to reduce rodenticides, even if you can’t eliminate them.”

This approach enabled the New York State Raptors Act of 2025 which bans online and retail-store sale of SGARs and “prohibits the use of either a first-generation anticoagulant rodenticide or a second-generation anticoagulant rodenticide within five hundred feet of a wildlife habitat area.”

Biologists complain that recovery projects for island wildlife are hampered by brodifacoum’s vile reputation acquired by gross public abuse on mainlands throughout the world. They report that brodifacoum, deployed in grain bait by wildlife professionals, is the only known way to eradicate invasive rodents from islands to restore native wildlife. And they warn that any ban on brodifacoum must not include its use by wildlife professionals for this specific purpose. “Bring us something else that will work; we will be the first to adopt it,” says Island Conservation’s Gregg Howald.

Partial, Possible Solutions

A wildlife-safe, pet-safe chemical contraceptive designed for rats called ContraPest has been developed by the U.S. biotech company SenesTech and approved by EPA. Some field data suggest a 90% population reduction within a year. But ContraPest doesn’t cause permanent sterility. Like human birth-control pills, it has to be continually ingested. So, its potential for widespread control is limited.

An emerging class of third-generation rodenticides may eventually provide some relief. They are being designed to reduce secondary poisonings of nontarget wildlife and minimize bioaccumulation while retaining lethality for rodents. They’re not yet named or commercially available. Some are being tested in pilot programs. At this writing, their safety and effectiveness are undetermined.

In a few areas, barn owls are being used as a hoped-for alternative to SGARs. In Australia, for example, a project in Northern Rivers, New South Wales shows some potential for reducing rat populations. For the last ten years, the “Owls Eat Rats” initiative has been installing barn-owl roosts and nest boxes in macadamia orchards.

“[Barn owls] move in, they breed and they hunt, and each breeding event takes about a thousand rats out of the system,” Alastair Duncan, founder of Owls Eat Rats, told ABC Rural News. “We’re finding that ninety percent [of regurgitated-pellet content is from] rats and the rest [from] house mice, which are a really significant pest in the agriculture industry.” In June 2025, Owls Eat Rats was granted $50,000 by the Taronga Zoo.

In California’s Napa Valley, grape growers are putting up nest boxes to attract barn owls for vole and gopher control. Funded by the Agricultural Research Institute, scientists from the University of California and California Polytechnic State University have been assessing results.

With remote video cameras, the team found that the average barn owl family consumes between 3,000 and 4,000 rodents per year, mostly gophers, voles and mice. Team data show that gopher activity is lowest in vineyards with barn owl nest boxes.

“Barn owls do not just kill rodents; they scare them, too,” report team members Drs. Matthew Johnson and Daniel Karp. “Recent work in Napa Valley shows that on vineyards heavily hunted by barn owls, voles and mice are fearful and minimize their movements, eating fewer seeds in experimentally deployed seed trays and appearing less frequently on remote cameras.”

If you have a rat or mouse problem, don’t make it worse by poisoning rodent-eating raptors and mammals. But predators alone can’t solve your problem because these rodents are vastly more fecund.

Bird feeders are also rat and mouse feeders, so clean up seeds spilled by birds. Inspect the outside perimeter of your house for rodent entrances. Our 250-year-old cellar was a rat haven until I found a narrow, leaf-concealed tunnel leading to it from our terrace. I filled the tunnel with an entire wheelbarrow-load of cement, ending our infestation.

Use metal garbage bins and keep them tightly sealed. If you compost garbage, keep the composter far from your house. If you have a vegetable garden, compost all unharvested produce. Never compost meat or fat. Inside your house, use snap traps or battery-powered electrocuting traps. Peanut butter is a far more effective bait than cheese. Do not use glue traps. They’re inhumane. What’s more, rats will extricate themselves, leaving most of their fur. Don’t set traps outside your house because you’ll kill small nontarget mammals and birds.

Bills to ban mainland use of SGARs have been introduced in Connecticut, New York, Massachusetts, Oregon and Washington. For the most part, they mirror California’s model, focusing on wildlife protection, non-target poisoning, and ecological risk. If you live in one of these states, lobby your state legislators to support these bills. If you don’t live in one of these states, lobby your local, state and U.S. legislators for town, state and national bans on online sale and mainland use of SGARs.

Finally, write a letter to Administrator U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20460. Include your name, organization if applicable, and contact information. State your position — “opposition to online sale and mainland use of SGARs” If you have expertise, mention it. Reiterate your main points. Thank the EPA for the opportunity to comment. Include hardcopy text of this piece; links tend to get ignored.

Ted Williams, a former information officer for the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, serves on the Circle of Chiefs of the Outdoor Writers Association of America. He writes exclusively about wildlife.