Two years ago in November, voters in California approved a ballot measure to ban the sale of animal products that come from pigs, laying hens, and veal calves kept in cages or crates barely larger than their bodies. In Florida, the hub of the national greyhound racing industry, citizens voted to shut down the state’s 12 racing facilities by the end of 2020.

These were extraordinary wins and very tangible gains for animals. We put our shoulder into them both.

For the first time since 1988, there will not be any citizen initiative on any statewide ballot in an even year to stop some form of animal cruelty. It reminds me what a transformational tool the citizen initiative has been in the contemporary era of animal protection, and what a crucial role animal protection ballot measures have played in addressing the toughest issues in our field.

These initiatives have put animal issues in the media, on voters’ minds, and on the national agenda. During the last three decades, no movement has been more successful in using the initiative process than ours. We must not let one more election cycle pass without major animal welfare reforms on the ballot in cases where legislators and corporations fail to act on necessary, popular reforms.

When I was with The Fund for Animals in 1990, I played a very modest role in a ballot initiative in California to ban the trophy hunting of mountain lions. Prompted by a strong grassroots campaign led by the Mountain Lion Foundation, voters approved the measure – the first successful statewide ballot measure for animals in decades. In 1992, as executive director of The Fund, I initiated a measure in Colorado to ban bear baiting or hounding or any kind of spring bear hunting, and it won in a landslide.

Then after joining the Humane Society of the U.S. in 1994, and with the support of so many donors, colleagues, and other organizations, I worked with professional colleagues to help initiate and pass some 25 ballot measures over the next quarter century, while also defeating a dozen efforts by hunting and agribusiness interests to restrict the use of the initiative process for animal welfare purposes.

These laws have arguably been the most consequential means of advancing landmark animal welfare reforms; breaking the hold of private industry and government lording over agriculture, hunting, and trapping policies in the states; and, in some cases, putting us on a path to achieve national bans on cruel practices, such as cockfighting and greyhound racing.

Starting with a ban on gestation crates in 2002, a series of our ballot measures imposed the first set of restrictions on the extreme confinement of animals on factory farms. Our movement has been undefeated since then in advancing anti-confinement measures. Today, more than 250 major retailers — from McDonald’s to Walmart to Target — have announced policies to phase out their purchasing of animal products coming from pigs and laying hens kept in small cages and crates.

Five successful initiatives to ban the use of body-gripping traps broke the hold that the wildlife management establishment had on this form of cruel, commercial killing. The same was true with a series of efforts to ban bear baiting, hounding of bears and mountain lions, and other extreme trophy hunting practices. In getting voters to reject trophy hunting and trapping of wolves in Michigan, we proved that the attempts by the wildlife management profession to hunt these carnivores did not pass the smell test with the public. A referendum to maintain a ban on dove hunting — which also passed in a landslide vote in Michigan — revealed that using these gentle, ground-feeding birds as animated targets was morally unacceptable.

While we won many of those initiatives, we lost a few too, including in Idaho and Maine on bear baiting and hounding, and much more work remains in the wildlife management domain.

We banned cockfighting in Arizona, Missouri, and Oklahoma, setting us up to eliminate the practice in Louisiana and New Mexico and then enabling us to pass federal legislation to ban animal fighting in the U.S. territories.

GREY2K USA led two winning ballot measures, in Massachusetts and Florida, putting greyhound racing on a path toward elimination in the U.S. A generation ago, there were 60 tracks in the United States, and by the end of this year, there will be four.

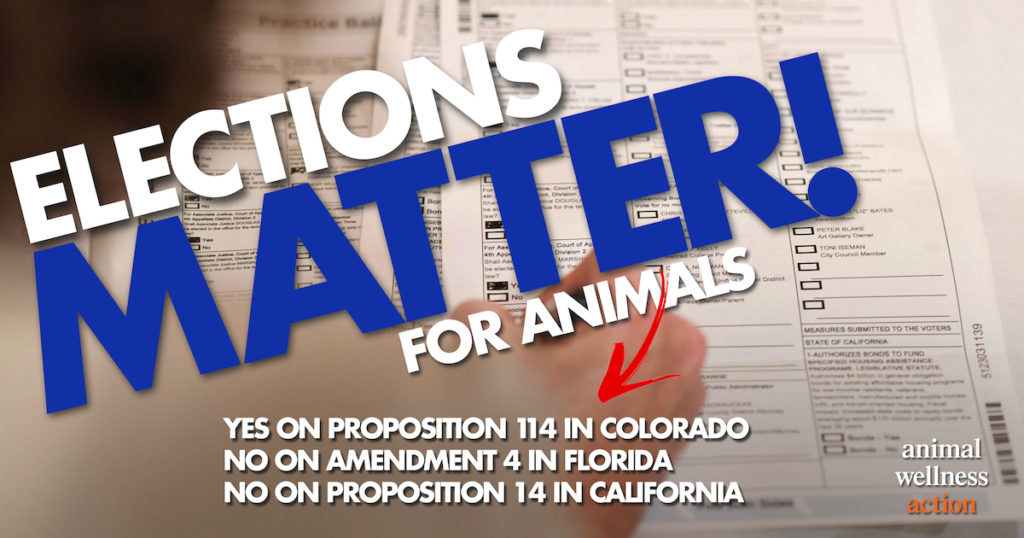

While there are no big anti-cruelty ballot measures on state ballots this year, there are some issues that warrant the urgent attention of animal advocates in three states.

Yes on Proposition 114 in Colorado

Animal Wellness Action urges support of Colorado Proposition 114. This measure would bring wolves back to Colorado, after they had been extirpated from the state by ranchers and others who wanted them cleansed from the landscape. Wolves are slowly reclaiming their range in the West, and voter approval of this measure would direct the state to restore this keystone predator to a major Rocky Mountain state. It merits the support of animal activists, who will then have to campaign mightily to preserve protections for them once the wolves are established. Safari Club International and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation are providing the bulk of the money in opposition to the measure.

No on Amendment 4 in Florida

Animal Wellness Action is urging a “No” vote on Amendment 4 on this year’s ballot, charging that the measure would make it all but impossible to pass statewide ballot measures by amending the state constitution to require two votes in two separate elections that each require supermajority thresholds of 60 percent. Corporations or individuals have spent more than $9 million to qualify and promote the measure, yet they have successfully concealed their economic interest.

Ballot measures have been a crucial tool for protecting greyhounds, animals on factory farms, and marine life.

No on Proposition 14 in California

Proposition 14 would be a massive expense to the state and trigger a catastrophic amount of animal testing for new drug development. Prop 14 issues $5.5 billion in general obligation bonds for the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) with additional repayment costs of $2.3 billion. Voters approved a $3-billion investment in a stem-cell measure in 2004, yet grandiose promises have been unfulfilled since that time and boosters of the measure are seeking nearly twice the money allocated in the original measure. The proposition omits any mention of funding animal research, yet existing FDA regulations require animal tests (rodent and non-rodents, and the latter typically means dogs or primates) before testing the drug in human clinical trials.

Elections matter. Lawmakers have sway over an immense array of animal issues. And occasionally voters get to weigh in on major issues affecting animals. We must never neglect to use this tool when we are out of other options. And please be sure to watch for our candidate endorsements in federal races in the coming days.