Betrayal of the Eagles: How Federal Officials Greenlight Illegal Wildlife Sacrifice

Despite clear legal protections, U.S. agencies are authorizing the capture, torture, and killing of bald and golden eagles on public lands — without public consent or oversight.

by Ted Williams

You can listen to an AI-generated reading of this story here:

In America, freedom of religious belief is sacrosanct, guaranteed by the First Amendment of our Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof … .”

There is, however, no such guarantee for religious practice. Some religious practices are accepted by Americans and protected by federal law, such as attempting to send smoke heavenward with attached prayers by burning incense in pots swung by believers. Other religious practices are anathema to Americans and prohibited by federal law, such as attempting to send sacrifices heavenward by burning dogs and house cats in fires prepared by believers.

So it is perplexing that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — and now even the National Park Service — facilitate ritualistic torture and sacrifice of wild raptors belonging to all Americans, despite the fact that Congress saw fit to protect these birds under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

Under exemptions for both laws, the USFWS allows the Hopi tribe in Arizona to torture and sacrifice golden eagles and red-tailed hawks it captures on public lands. And NPS allows the Jemez Pueblo tribe in New Mexico to torture and sacrifice bald or golden eagles (so far, one of either species) it captures on the Valles Caldera National Preserve.

Here’s how the ritual works: Fledgling eagles and hawks are taken from their nests in spring, tied to adobe rooftops, fed bits of rabbits and mice, presented with children’s toys, and told how honored they should feel to be chosen for the ritual.

The eagles and hawks, explain Hopi elders, are spoiled like adored children until the Niman, or Home Dance, in mid-July. Then they’re smothered with blankets or corn meal so they may travel to the “other world” and tell the gods about their kind and generous treatment.

But the birds may be delivering a different message. They seem unenthused about being restrained under the hot sun for almost three months. Sometimes their eyelids are sewn shut, and straps around their feet wear away skin and sinew.

In ceremonies to encourage renesting, feathers from sacrificed eagles are scattered under aeries. But, if the practice ever worked, its effectiveness has taken wing because birds keep getting removed and killed.

In 2022, the USFWS issued a yearly take permit to the Hopis for 50 red-tailed hawks until March 31, 2026. And it issued them a “take” permit for 40 golden eagles.

In 2023, the USFWS issued a take permit to the Jemez Pueblos for eight eagles (an undisclosed mix of balds and goldens).

In 2023, the NPS issued a take permit to the Jemez Pueblos for one eagle (bald or golden) from the Valles Caldera National Preserve (from the eight authorized by USFWS).

In 2024, the USFWS issued another Hopi take permit for 40 golden eagles and a new take permit to the Jemez Pueblos for eight more eagles (an undisclosed mix of balds and goldens).

In 2025, USFWS will apparently issue a new take permit to the Jemez Pueblos for eight more eagles (an undisclosed mix of balds and goldens).

The USFWS monitoring of eagle take has been casual and infrequent.

It is perplexing that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — and now even the National Park Service — facilitate ritualistic torture and sacrifice of wild raptors belonging to all Americans, despite the fact that Congress saw fit to protect these birds under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

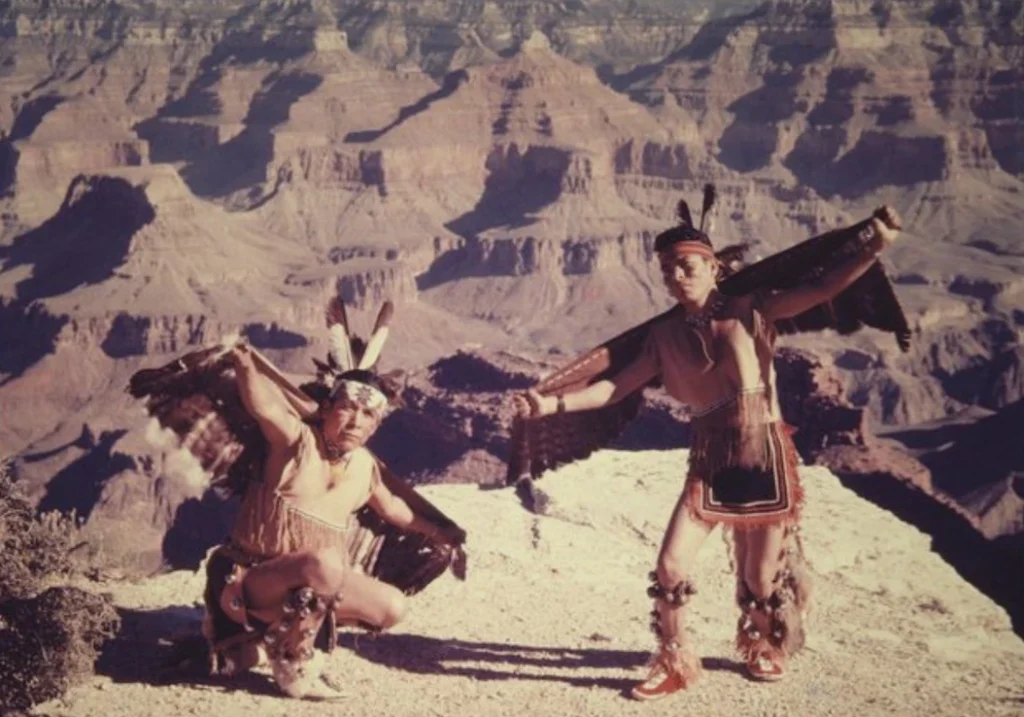

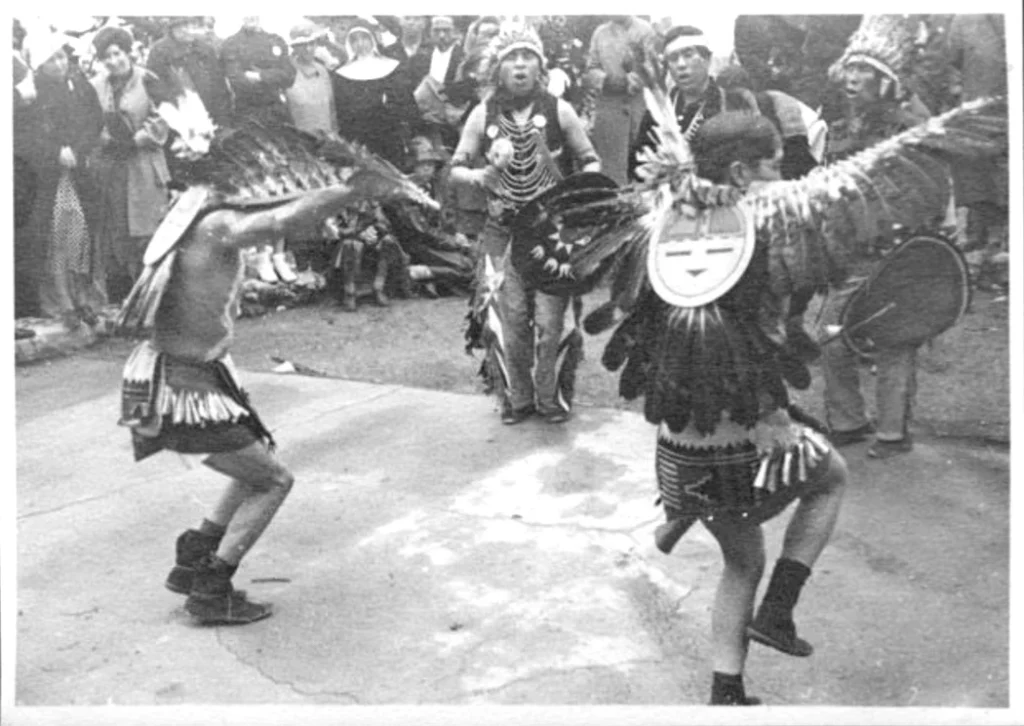

Hopi Indian Eagle Dancers. Still living in their pueblos on lofty mesas, these Indians have for centuries dressed like soaring eagles to dance their ritual steps. Credit: Josef Muench, with Northern Arizona University Cline Library

Federal agencies open sanctuaries to eagle capture, sacrifice, and suffering

Eagles are already compromised by ingesting lead bullet fragments from gut piles and dead animals left by hunters. A study published in the February 17, 2022, issue of Science found that “almost half” of all bald and golden eagles sampled “had chronic, toxic levels of lead” that appeared “high enough to suppress population growth in both species.” Other limiting factors include wind turbines and climate change. The federal government fails to consider any of these when issuing eagle take permits.

Now, for the first time, the NPS has opened up a park unit — the Valles Caldera National Preserve in New Mexico — to eagle take. Flouting long-standing NPS regulations and federal law, it has set a dangerous precedent by authorizing the Jemez Pueblos to capture and sacrifice a bald or golden eagle.

The NPS Organic Act requires the agency to “conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wild life” of all units in which hunting is not authorized, “leave[ing] them unimpaired,” a provision that may be waived only by Congress. What’s more, the National Environmental Policy Act [NEPA] requires that: 1. NPS notify the public about actions that would affect a unit’s environment, and 2. that the public have an opportunity to comment on such actions.

Biden’s NPS director Chuck Sams (Dec. 16, 2021-Jan. 20, 2025) shielded his decision and Environmental Assessment from the public, including the entire NPS other than his immediate staff, until implementation.

Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility tracks eagle take permits with annual Freedom of Information (FOIA) requests. But it only heard about the NPS eagle-take permit from the local group Caldera Action.

“The NPS regional office was left out of the loop,” said PEER’s Counsel Jeff Ruch, who co-founded the outfit 32 years ago. “The decision and EA came directly from D.C. headquarters. In thirty-four years of watching, I’ve never seen the director of an agency sign off on an EA for a specific park thing.”

“The implications are enormous,” said Frank Buono, retired Deputy Superintendent of Joshua Tree National Park in California. “The Jemez Pueblos can just as easily take eagles from Grand Canyon National Park because nothing legally distinguishes taking wildlife from one and not the other. And word will spread to other tribes. If the Jemez Pueblos can take eagles from the Valles Caldera National Preserve, why not the Ogalala and Yankton Sioux from Badlands National Park, or the Chippewa from Voyageurs National Park?”

Ruch added: “Our concern is that this could become a regular practice. The Biden administration did nothing when these activities were going on. Biden’s Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland and NPS director Chuck Sams had scores of ‘co-stewardship agreements’ [with tribes]. For years we’ve tried to get these unearthed. We’ve gone park to park to FOIA them, but nowhere are they available. There’s been no NEPA work done on any of what’s being proposed.”

On February 23, 2024, a dozen former high-ranking government officials and scientists responded to the NPS decision with a letter of protest to then Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. They were ignored. PEER also protested and was also ignored.

Buono, one of the signers, told me this: “NPS director Chuck Sams believed that the parks are no longer sanctuaries for eagles but sanctuaries for tribal uses. These parks are islands of sanctuary, and they form the basis for augmenting and sustaining eagle populations outside the parks. Sams did not see the parks as any different from outside lands. He and his top NPS civil service professionals, like Ray Sauvajot [Associate Director for all natural resource issues in the NPS system], didn’t care to give notice to the public which owns the parks. Instead, they drafted a quick and dirty Environmental Assessment that the public never saw until the approval was granted. The public was contemptuously frozen out of one of the most consequential and unprecedented decisions in recent park system history.”

Another signer of the protest letter to Secretary Haaland was Elaine Leslie, who, while serving as chief of NPS’s Biological Resources Division, drafted documents — approved by her superiors — stating that NPS would never issue eagle take permits.

“Many tribes have evolved and adapted to continue traditional practices without inflicting harm on the very resource that they profess to honor,” Leslie said. National Park Service units are, by law, set aside to protect and conserve the natural and cultural resources within for all Americans. We cannot turn a blind eye to the collection and capture, inhumane raising, and finally the smothering to death of raptors as an acceptable practice. And even more so when it means these majestic birds-symbols of the west, the winds, and the sky, and even our national bird, are snatched from our nation’s most protected lands only to suffer and be eliminated. This is not what the American public expects or should tolerate. What species is next? Grizzlies, wolves, or others deemed culturally significant?”

Hopi Indian Eagle Dancers. Credit: Josef Muench, with Northern Arizona University Cline Library

“Many tribes have evolved and adapted to continue traditional practices without inflicting harm on the very resource that they profess to honor,” said Elaine Leslie, former chief of biological resources for the U.S. National Park Service.

We cannot turn a blind eye to the collection and capture, inhumane raising, and finally the smothering to death of raptors as an acceptable practice.

From ‘no’ to ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ on eagle kills

Interior tried once before, and failed, to authorize eagle take on a national park unit.

In May 1999 the Hopis attempted to collect golden eagle nestlings from Wupatki National Monument in Arizona. They were turned away by the NPS, which cited regulations that “prohibit take of living or dead wildlife, including take for religious or ceremonial purposes unless specifically provided for in law or as a treaty right.” No law or treaty ever entitled the Hopi to capture and sacrifice park wildlife.

Raptor biologist David Ellis of the U.S. Geological Survey told me this at the time: “The biggest problem the eagle has on the Hopi and Navajo reservations [which occupy about 20 percent of Arizona] is overgrazing. The primary productivity has been destroyed, so there aren’t very many jackrabbits or cottontails. The eagles are hurting already, and then they get hit by Hopi… I view the Hopi reservation as an aquiline black hole.”

When the Hopis were denied Wupatki eagle take permits, tribal chairman Wayne Taylor proclaimed via press release that the tribe had “never experienced a situation where [members] were so mistreated by park officials.” He complained in writing to monument superintendent Sam Henderson, who replied that his agency didn’t have legal authority to allow the Hopi to collect wildlife.

Taylor then sent a letter to Henderson’s boss, John Cook, director of the Park Service’s Intermountain Region, who repeated Henderson’s explanation. “We do not agree with your argument,” Henderson wrote.

Next, Taylor wrote Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, asserting that the Park Service was denying “fundamental Hopi religious rights.” Babbitt instructed acting NPS director Linda Canzanelli to respond.

On July 26, 1999, Canzanelli reiterated to Taylor everything Henderson and Cook had written, adding that the Hopi USFWS eagle-collecting permit “does not override the National Park Service’s regulation.”

But that August, Don Barry, Clinton’s Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks, went rafting with Taylor on the Colorado River and got an earful about how the NPS was abusing the Hopi Nation.

According to documents obtained by PEER under the Freedom of Information Act, Barry suggested at a staff meeting that the robbing of eagle nests at Wupatki should proceed on a “don’t ask/don’t tell” basis since the Hopis probably had been doing it all along without Interior’s knowledge or regard for federal law.

Apparently, Barry’s speculation was correct. When I asked Taylor’s chief of staff, Eugene Kaye, if tribal members had secretly been collecting eagle nestlings in Wupatki, he said he was “pretty sure” they had. “Why shouldn’t they?” he demanded.

The only environmental group that dared to confront Interior and the Hopi was PEER, though the National Audubon Society did allow me to report on the issue in Audubon magazine (“Golden Eagles for the Gods,” March-April, 2001). “We haven’t seen anything this crude in quite a while,” Ruch told me. To Barry he wrote: “Your conduct and involvement in this issue has been nothing less than disgraceful.”

With that, Clinton’s Interior Department hatched a special rule directing the NPS to permit the Hopis to take golden eagles from Wupatki. (Bald eagles were still listed as endangered.)

But the notice didn’t get published in the Federal Register until January 22, 2001, two days after George W. Bush took office. His administration never finalized the rule.

Now NPS finally has succeeded in opening the park system to wildlife take.

‘What kind of gods want eagles dead?’

Other tribes and a large element of the Hopi Nation take a dim view of eagle torture and sacrifice. The Navajo Nation keeps complaining about trespassing Hopis depleting its eagle population.

In 2012, the Eastern Shoshones, who revere free, living eagles as messengers to the creator and are adamant about protecting them, sued the Interior Department for denying their fundamental religious rights by permitting the Arapaho to kill bald eagles on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, shared by the two tribes. The federal court ruled that the Arapahos must restrict their eagle killing to lands outside the reservation.

According to some Hopis, eagle and hawk sacrifice should be banned, as was child sacrifice, from which anthropologists believe the raptor ritual may have derived.

A member of the Hopi Eagle Clan — which also reveres free, living eagles — asked this of a USFWS special agent working undercover: “How would you like to be chained in the sun for 80 days?” The subject then revealed that members of the Hopi First Mesa (the plateau on which the Eagle Clan lives) sometimes sneak up to the Second Mesa and release birds.

Hopi elders claim they need all the feathers they pluck from sacrificed eagles. Younger Hopis submit that the birds should be only partially plucked, then freed. But this, caution elders, would displease the gods.

“There are more than enough eagle feathers for all tribes as it is,” notes one outraged critic of raptor nest robbing and sacrifice, Wayne Pacelle, president and founder of Animal Wellness Action and the Center for a Humane Economy. “Tribes can acquire almost unlimited numbers of feathers from the USFWS Eagle Repository near Denver, Colorado. The torture and sacrifice of eagles and hawks is cruelty to wildlife and should not be excused as a cultural prerogative, especially given the alternatives.”

Americans and their legal system acknowledge the rights of domestic dogs and cats. What about the rights of wild raptors? And what about the rights of Americans — red, white, black, young, old and yet unborn — who cherish or will cherish living raptors? No Americans, including native Americans, should get a pass on wildlife protection laws and animal cruelty laws merely because of their “faith.”

As the Eastern Shoshones and the Hopi Eagle Clan might put it: What kind of gods want eagles and hawks dead and plucked instead of soaring in our spacious skies?

Ted Williams, a lifelong hunter and angler, is a former information officer for the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. He writes exclusively about fish and wildlife.